Chi-squared Tests

2026-02-04

Last updated: 2026-02-04

Checks: 7 0

Knit directory: muse/

This reproducible R Markdown analysis was created with workflowr (version 1.7.1). The Checks tab describes the reproducibility checks that were applied when the results were created. The Past versions tab lists the development history.

Great! Since the R Markdown file has been committed to the Git repository, you know the exact version of the code that produced these results.

Great job! The global environment was empty. Objects defined in the global environment can affect the analysis in your R Markdown file in unknown ways. For reproduciblity it’s best to always run the code in an empty environment.

The command set.seed(20200712) was run prior to running

the code in the R Markdown file. Setting a seed ensures that any results

that rely on randomness, e.g. subsampling or permutations, are

reproducible.

Great job! Recording the operating system, R version, and package versions is critical for reproducibility.

Nice! There were no cached chunks for this analysis, so you can be confident that you successfully produced the results during this run.

Great job! Using relative paths to the files within your workflowr project makes it easier to run your code on other machines.

Great! You are using Git for version control. Tracking code development and connecting the code version to the results is critical for reproducibility.

The results in this page were generated with repository version 393faf7. See the Past versions tab to see a history of the changes made to the R Markdown and HTML files.

Note that you need to be careful to ensure that all relevant files for

the analysis have been committed to Git prior to generating the results

(you can use wflow_publish or

wflow_git_commit). workflowr only checks the R Markdown

file, but you know if there are other scripts or data files that it

depends on. Below is the status of the Git repository when the results

were generated:

Ignored files:

Ignored: .Rproj.user/

Ignored: data/1M_neurons_filtered_gene_bc_matrices_h5.h5

Ignored: data/293t/

Ignored: data/293t_3t3_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: data/293t_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: data/5k_Human_Donor1_PBMC_3p_gem-x_5k_Human_Donor1_PBMC_3p_gem-x_count_sample_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/5k_Human_Donor2_PBMC_3p_gem-x_5k_Human_Donor2_PBMC_3p_gem-x_count_sample_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/5k_Human_Donor3_PBMC_3p_gem-x_5k_Human_Donor3_PBMC_3p_gem-x_count_sample_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/5k_Human_Donor4_PBMC_3p_gem-x_5k_Human_Donor4_PBMC_3p_gem-x_count_sample_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/97516b79-8d08-46a6-b329-5d0a25b0be98.h5ad

Ignored: data/Parent_SC3v3_Human_Glioblastoma_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.tar.gz

Ignored: data/brain_counts/

Ignored: data/cl.obo

Ignored: data/cl.owl

Ignored: data/jurkat/

Ignored: data/jurkat:293t_50:50_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: data/jurkat_293t/

Ignored: data/jurkat_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: data/pbmc20k/

Ignored: data/pbmc20k_seurat/

Ignored: data/pbmc3k.csv

Ignored: data/pbmc3k.csv.gz

Ignored: data/pbmc3k.h5ad

Ignored: data/pbmc3k/

Ignored: data/pbmc3k_bpcells_mat/

Ignored: data/pbmc3k_export.mtx

Ignored: data/pbmc3k_matrix.mtx

Ignored: data/pbmc3k_seurat.rds

Ignored: data/pbmc4k_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: data/pbmc_1k_v3_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/pbmc_1k_v3_raw_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/refdata-gex-GRCh38-2020-A.tar.gz

Ignored: data/seurat_1m_neuron.rds

Ignored: data/t_3k_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: r_packages_4.4.1/

Ignored: r_packages_4.5.0/

Untracked files:

Untracked: .claude/

Untracked: CLAUDE.md

Untracked: analysis/bioc.Rmd

Untracked: analysis/bioc_scrnaseq.Rmd

Untracked: analysis/chick_weight.Rmd

Untracked: analysis/likelihood.Rmd

Untracked: bpcells_matrix/

Untracked: data/Caenorhabditis_elegans.WBcel235.113.gtf.gz

Untracked: data/GCF_043380555.1-RS_2024_12_gene_ontology.gaf.gz

Untracked: data/SeuratObj.rds

Untracked: data/arab.rds

Untracked: data/astronomicalunit.csv

Untracked: data/femaleMiceWeights.csv

Untracked: data/lung_bcell.rds

Untracked: m3/

Untracked: women.json

Unstaged changes:

Modified: analysis/isoform_switch_analyzer.Rmd

Modified: analysis/linear_models.Rmd

Note that any generated files, e.g. HTML, png, CSS, etc., are not included in this status report because it is ok for generated content to have uncommitted changes.

These are the previous versions of the repository in which changes were

made to the R Markdown (analysis/chi.Rmd) and HTML

(docs/chi.html) files. If you’ve configured a remote Git

repository (see ?wflow_git_remote), click on the hyperlinks

in the table below to view the files as they were in that past version.

| File | Version | Author | Date | Message |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rmd | 393faf7 | Dave Tang | 2026-02-04 | Update |

| html | 503ceec | Dave Tang | 2025-11-14 | Build site. |

| Rmd | dddb710 | Dave Tang | 2025-11-14 | Chi-squared tests |

Introduction

The chi-squared (\(\chi^2\)) test is one of the most widely used statistical tests for categorical data. There are two main types:

- Chi-squared test of independence: Tests whether two categorical variables are related

- Chi-squared goodness of fit test: Tests whether observed frequencies match expected frequencies

Common applications include:

- Is smoking related to lung cancer?

- Is gender related to voting preference?

- Does a die produce fair outcomes?

- Is a treatment associated with recovery?

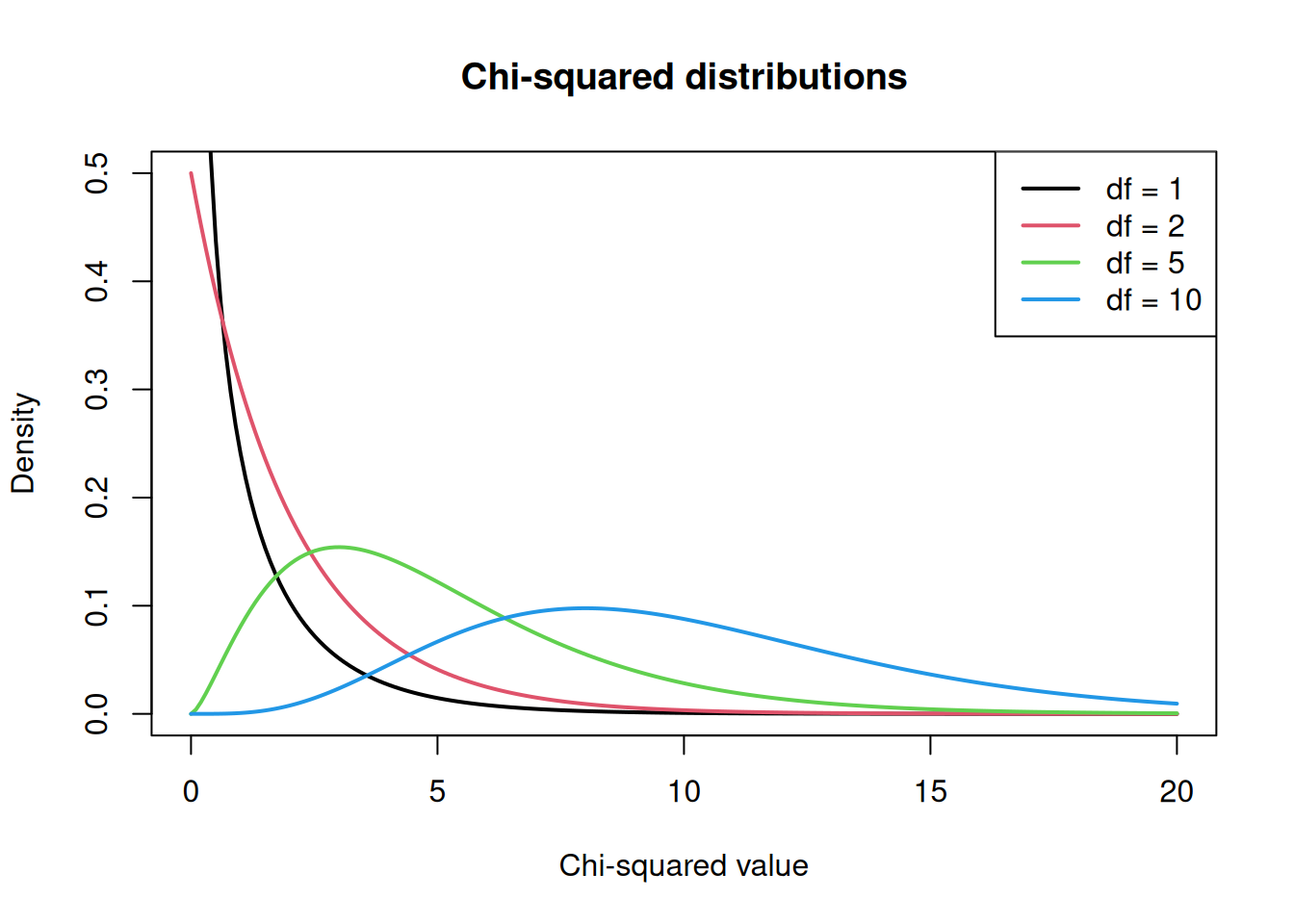

The Chi-Squared Distribution

The chi-squared distribution arises when summing squared standard normal random variables. It has one parameter: degrees of freedom (df), which determines its shape.

x <- seq(0, 20, length = 200)

plot(x, dchisq(x, df = 1), type = "l", lwd = 2, col = 1,

ylim = c(0, 0.5), ylab = "Density", xlab = "Chi-squared value",

main = "Chi-squared distributions")

lines(x, dchisq(x, df = 2), lwd = 2, col = 2)

lines(x, dchisq(x, df = 5), lwd = 2, col = 3)

lines(x, dchisq(x, df = 10), lwd = 2, col = 4)

legend("topright", legend = paste("df =", c(1, 2, 5, 10)),

col = 1:4, lwd = 2)

As degrees of freedom increase, the distribution becomes more symmetric and shifts to the right.

Chi-Squared Test of Independence

This test determines whether there is a statistically significant association between two categorical variables.

Hypotheses

- Null hypothesis (\(H_0\)): The two variables are independent (no association)

- Alternative hypothesis (\(H_1\)): The two variables are not independent (there is an association)

The Test Statistic

The chi-squared statistic measures the discrepancy between observed and expected frequencies:

\[\chi^2 = \sum \frac{(O - E)^2}{E}\]

where:

- \(O\) = observed frequency in each cell

- \(E\) = expected frequency if variables were independent

The expected frequency for each cell is calculated as:

\[E = \frac{\text{row total} \times \text{column total}}{\text{grand total}}\]

Example 1: Smoking and Lung Cancer

Let’s test whether smoking is associated with lung cancer using a 2x2 contingency table.

data <- matrix(

c(60, 40, 30, 70),

nrow = 2,

byrow = TRUE

)

colnames(data) <- c("Cancer", "NoCancer")

rownames(data) <- c("Smoker", "NonSmoker")

data Cancer NoCancer

Smoker 60 40

NonSmoker 30 70Step 1: Calculate Expected Values

If smoking and cancer were independent, we would expect each cell to have:

\[E = \frac{\text{row total} \times \text{column total}}{\text{grand total}}\]

# Row and column totals

row_totals <- rowSums(data)

col_totals <- colSums(data)

grand_total <- sum(data)

row_totals Smoker NonSmoker

100 100 col_totals Cancer NoCancer

90 110 grand_total[1] 200# Calculate expected values

expected <- outer(row_totals, col_totals) / grand_total

expected Cancer NoCancer

Smoker 45 55

NonSmoker 45 55For example, the expected count for Smoker + Cancer is: \((100 \times 90) / 200 = 45\)

Step 2: Calculate the Chi-Squared Statistic

# Chi-squared = sum of (observed - expected)^2 / expected

chi_sq <- sum((data - expected)^2 / expected)

chi_sq[1] 18.18182Step 3: Run the Test

result <- chisq.test(data)

result

Pearson's Chi-squared test with Yates' continuity correction

data: data

X-squared = 16.99, df = 1, p-value = 3.758e-05Interpreting the Output

- X-squared = 16.99: The test statistic measuring how different observed values are from expected values

- df = 1: Degrees of freedom = (rows - 1) x (columns - 1) = 1 for a 2x2 table

- p-value = 3.76e-05: Probability of seeing this extreme a result if the null hypothesis were true

Since the p-value is very small (< 0.05), we reject the null hypothesis and conclude that smoking and lung cancer are associated.

Accessing Test Components

The test object contains useful information:

# Observed values

result$observed Cancer NoCancer

Smoker 60 40

NonSmoker 30 70# Expected values (same as our manual calculation)

result$expected Cancer NoCancer

Smoker 45 55

NonSmoker 45 55# Residuals: (observed - expected) / sqrt(expected)

result$residuals Cancer NoCancer

Smoker 2.236068 -2.0226

NonSmoker -2.236068 2.0226Residuals show which cells contribute most to the chi-squared statistic. Large positive residuals indicate more observations than expected; large negative residuals indicate fewer.

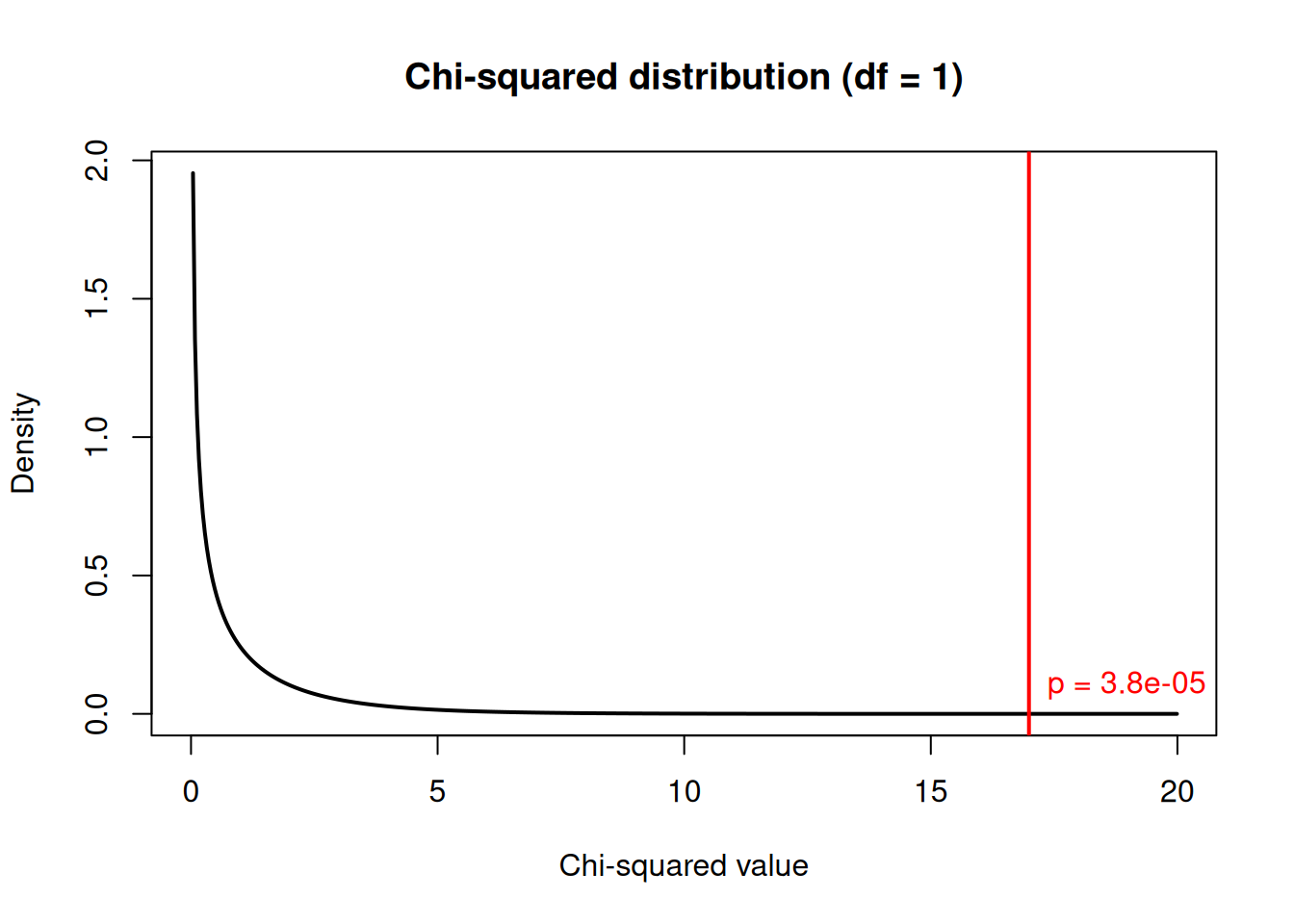

Visualising the Result

x2 <- result$statistic

df <- result$parameter

x <- seq(0, x2 + 3, length = 500)

plot(x, dchisq(x, df), type = "l", lwd = 2,

ylab = "Density", xlab = "Chi-squared value",

main = paste0("Chi-squared distribution (df = ", df, ")"))

abline(v = x2, col = "red", lwd = 2)

# Shade the rejection region

x_shade <- seq(x2, x2 + 3, length = 100)

polygon(c(x_shade, rev(x_shade)),

c(dchisq(x_shade, df), rep(0, length(x_shade))),

col = rgb(1, 0, 0, 0.3), border = NA)

text(x2, 0.1, paste("p =", format.pval(result$p.value, digits = 2)),

pos = 4, col = "red")

| Version | Author | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 503ceec | Dave Tang | 2025-11-14 |

The red line shows our test statistic. The shaded area represents the p-value: the probability of getting a value this extreme or more extreme under the null hypothesis.

Example 2: Larger Contingency Table

Chi-squared tests work for tables larger than 2x2. Let’s examine the relationship between education level and job satisfaction:

# Create a 3x3 table

job_data <- matrix(

c(20, 25, 15, # High school

30, 40, 20, # Bachelor's

15, 30, 25), # Graduate

nrow = 3,

byrow = TRUE

)

colnames(job_data) <- c("Low", "Medium", "High")

rownames(job_data) <- c("HighSchool", "Bachelors", "Graduate")

job_data Low Medium High

HighSchool 20 25 15

Bachelors 30 40 20

Graduate 15 30 25result2 <- chisq.test(job_data)

result2

Pearson's Chi-squared test

data: job_data

X-squared = 5.1406, df = 4, p-value = 0.2732For a 3x3 table, df = (3-1) x (3-1) = 4.

# View expected values

round(result2$expected, 1) Low Medium High

HighSchool 17.7 25.9 16.4

Bachelors 26.6 38.9 24.5

Graduate 20.7 30.2 19.1The p-value of 0.273 suggests a marginally significant association between education and job satisfaction.

Example 3: No Association

To understand what “no association” looks like, let’s create data where the variables are independent:

set.seed(1984)

# Generate independent data

n <- 200

gender <- sample(c("Male", "Female"), n, replace = TRUE)

preference <- sample(c("Tea", "Coffee"), n, replace = TRUE)

indep_table <- table(gender, preference)

indep_table preference

gender Coffee Tea

Female 53 50

Male 51 46chisq.test(indep_table)

Pearson's Chi-squared test with Yates' continuity correction

data: indep_table

X-squared = 0.00028872, df = 1, p-value = 0.9864With a large p-value, we fail to reject the null hypothesis. There is no evidence of an association between gender and beverage preference in this simulated data.

Chi-Squared Goodness of Fit Test

This test compares observed frequencies to expected frequencies based on a theoretical distribution.

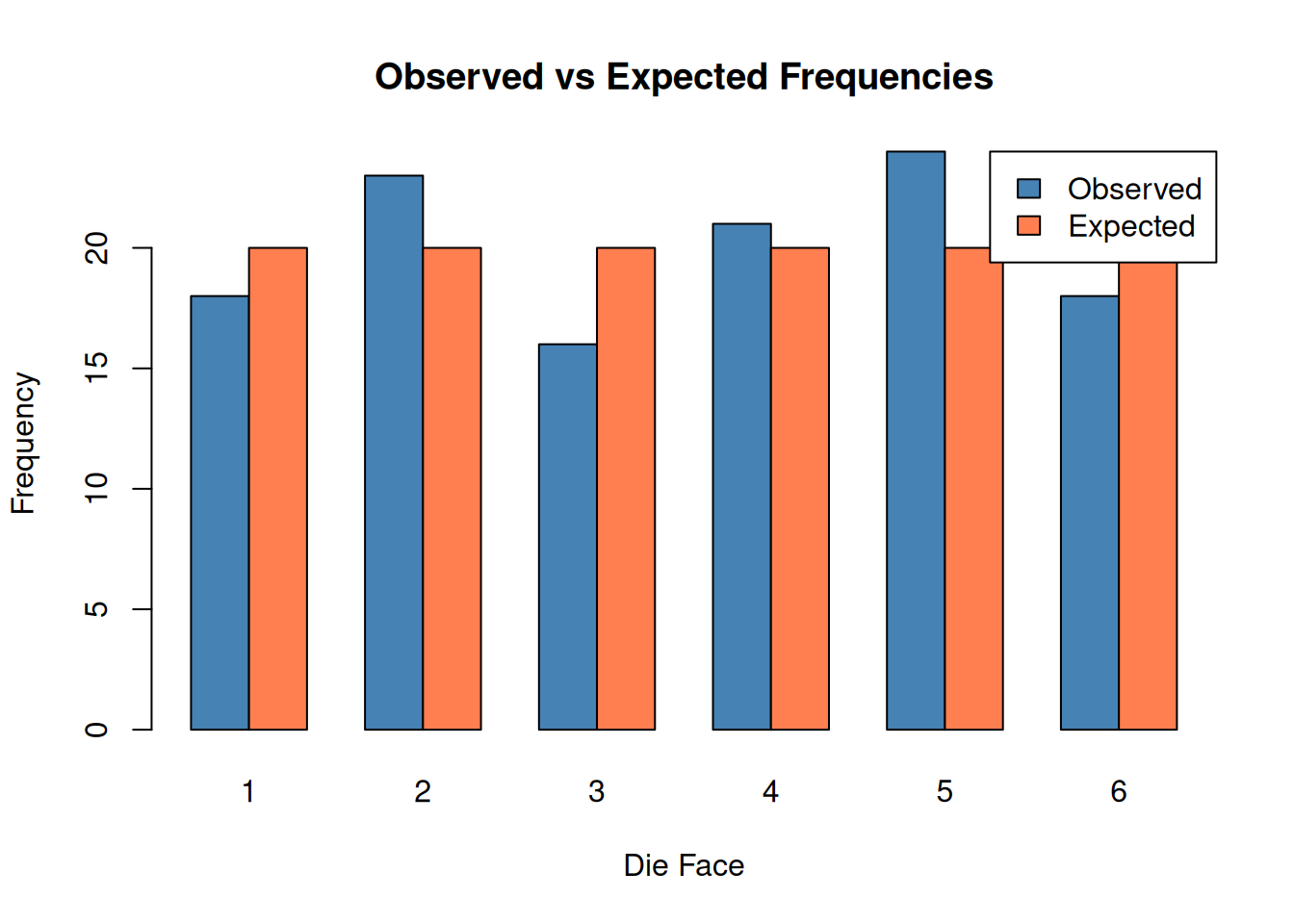

Example: Is a Die Fair?

Suppose we roll a die 120 times and observe the following counts:

observed <- c(18, 23, 16, 21, 24, 18)

names(observed) <- 1:6

# Expected: equal probability for each face

expected_prob <- rep(1/6, 6)

# Goodness of fit test

gof_result <- chisq.test(observed, p = expected_prob)

gof_result

Chi-squared test for given probabilities

data: observed

X-squared = 2.5, df = 5, p-value = 0.7765The large p-value suggests we cannot reject the hypothesis that the die is fair.

barplot(

rbind(observed, expected_prob * sum(observed)),

beside = TRUE,

col = c("steelblue", "coral"),

names.arg = 1:6,

xlab = "Die Face",

ylab = "Frequency",

main = "Observed vs Expected Frequencies",

legend.text = c("Observed", "Expected"),

args.legend = list(x = "topright")

)

Example: Testing a Genetic Ratio

In genetics, Mendel’s law predicts a 9:3:3:1 ratio for certain crosses. Let’s test whether observed data follows this ratio:

observed_plants <- c(315, 108, 101, 32)

names(observed_plants) <- c("Round-Yellow", "Round-Green",

"Wrinkled-Yellow", "Wrinkled-Green")

# Expected ratio 9:3:3:1

expected_ratio <- c(9, 3, 3, 1) / 16

mendel_test <- chisq.test(observed_plants, p = expected_ratio)

mendel_test

Chi-squared test for given probabilities

data: observed_plants

X-squared = 0.47002, df = 3, p-value = 0.9254The p-value of 0.925 indicates the observed data is consistent with the expected 9:3:3:1 ratio.

Assumptions and Conditions

The chi-squared test has several assumptions:

- Independence: Observations must be independent

- Random sampling: Data should come from a random sample

- Expected frequencies: All expected cell counts should be at least 5

Checking Expected Frequencies

# Check expected values

result$expected Cancer NoCancer

Smoker 45 55

NonSmoker 45 55# All expected values >= 5, so assumption is met

all(result$expected >= 5)[1] TRUEWhen Assumptions Are Violated

If expected frequencies are too small (< 5), consider:

- Fisher’s exact test: For 2x2 tables with small samples

- Combining categories: Merge cells to increase expected counts

- Simulation-based p-value: Use

chisq.test(..., simulate.p.value = TRUE)

# Small sample example

small_data <- matrix(c(3, 2, 1, 4), nrow = 2)

rownames(small_data) <- c("Treatment", "Control")

colnames(small_data) <- c("Success", "Failure")

small_data Success Failure

Treatment 3 1

Control 2 4# Chi-squared test warns about small expected values

chisq.test(small_data)Warning in chisq.test(small_data): Chi-squared approximation may be incorrect

Pearson's Chi-squared test with Yates' continuity correction

data: small_data

X-squared = 0.41667, df = 1, p-value = 0.5186# Use Fisher's exact test instead

fisher.test(small_data)

Fisher's Exact Test for Count Data

data: small_data

p-value = 0.5238

alternative hypothesis: true odds ratio is not equal to 1

95 percent confidence interval:

0.218046 390.562917

sample estimates:

odds ratio

4.918388 Effect Size: Cramer’s V

A significant p-value tells us an association exists, but not how strong it is. Cramer’s V measures effect size for chi-squared tests:

\[V = \sqrt{\frac{\chi^2}{n \times (k - 1)}}\]

where \(n\) is the sample size and \(k\) is the smaller of the number of rows or columns.

# Calculate Cramer's V for the smoking example

chi_sq <- result$statistic

n <- sum(data)

k <- min(nrow(data), ncol(data))

cramers_v <- sqrt(chi_sq / (n * (k - 1)))

cramers_vX-squared

0.291461 Interpretation guidelines for Cramer’s V:

| V | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 0.1 | Small effect |

| 0.3 | Medium effect |

| 0.5 | Large effect |

A Cramer’s V of 0.29 indicates a small to medium effect size. # Yates’ Continuity Correction

For 2x2 tables, R applies Yates’ continuity correction by default. This makes the test more conservative (larger p-values) but can be overly conservative with moderate sample sizes.

# With Yates' correction (default)

chisq.test(data)

Pearson's Chi-squared test with Yates' continuity correction

data: data

X-squared = 16.99, df = 1, p-value = 3.758e-05# Without Yates' correction

chisq.test(data, correct = FALSE)

Pearson's Chi-squared test

data: data

X-squared = 18.182, df = 1, p-value = 2.008e-05The uncorrected version gives a slightly smaller p-value. For large samples, the difference is negligible.

Summary

| Test | Purpose | R Function |

|---|---|---|

| Test of independence | Association between two categorical variables | chisq.test(table) |

| Goodness of fit | Compare observed to expected frequencies | chisq.test(x, p = prob) |

| Fisher’s exact test | Small samples (expected < 5) | fisher.test(table) |

Key points:

- Chi-squared tests assess relationships between categorical variables

- The test statistic measures how much observed differs from expected

- Larger chi-squared values indicate stronger evidence against independence

- Check that expected frequencies are at least 5

- Use Cramer’s V to measure effect size

- For small samples, use Fisher’s exact test instead

sessionInfo()R version 4.5.0 (2025-04-11)

Platform: x86_64-pc-linux-gnu

Running under: Ubuntu 24.04.3 LTS

Matrix products: default

BLAS: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/openblas-pthread/libblas.so.3

LAPACK: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/openblas-pthread/libopenblasp-r0.3.26.so; LAPACK version 3.12.0

locale:

[1] LC_CTYPE=en_US.UTF-8 LC_NUMERIC=C

[3] LC_TIME=en_US.UTF-8 LC_COLLATE=en_US.UTF-8

[5] LC_MONETARY=en_US.UTF-8 LC_MESSAGES=en_US.UTF-8

[7] LC_PAPER=en_US.UTF-8 LC_NAME=C

[9] LC_ADDRESS=C LC_TELEPHONE=C

[11] LC_MEASUREMENT=en_US.UTF-8 LC_IDENTIFICATION=C

time zone: Etc/UTC

tzcode source: system (glibc)

attached base packages:

[1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

other attached packages:

[1] knitr_1.50 lubridate_1.9.4 forcats_1.0.0 stringr_1.5.1

[5] dplyr_1.1.4 purrr_1.0.4 readr_2.1.5 tidyr_1.3.1

[9] tibble_3.3.0 ggplot2_3.5.2 tidyverse_2.0.0 workflowr_1.7.1

loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

[1] sass_0.4.10 generics_0.1.4 stringi_1.8.7 hms_1.1.3

[5] digest_0.6.37 magrittr_2.0.3 timechange_0.3.0 evaluate_1.0.3

[9] grid_4.5.0 RColorBrewer_1.1-3 fastmap_1.2.0 rprojroot_2.0.4

[13] jsonlite_2.0.0 processx_3.8.6 whisker_0.4.1 ps_1.9.1

[17] promises_1.3.3 httr_1.4.7 scales_1.4.0 jquerylib_0.1.4

[21] cli_3.6.5 rlang_1.1.6 withr_3.0.2 cachem_1.1.0

[25] yaml_2.3.10 tools_4.5.0 tzdb_0.5.0 httpuv_1.6.16

[29] vctrs_0.6.5 R6_2.6.1 lifecycle_1.0.4 git2r_0.36.2

[33] fs_1.6.6 pkgconfig_2.0.3 callr_3.7.6 pillar_1.10.2

[37] bslib_0.9.0 later_1.4.2 gtable_0.3.6 glue_1.8.0

[41] Rcpp_1.0.14 xfun_0.52 tidyselect_1.2.1 rstudioapi_0.17.1

[45] farver_2.1.2 htmltools_0.5.8.1 rmarkdown_2.29 compiler_4.5.0

[49] getPass_0.2-4