Introduction to the Fourier Transform

2026-02-02

Last updated: 2026-02-02

Checks: 7 0

Knit directory: muse/

This reproducible R Markdown analysis was created with workflowr (version 1.7.1). The Checks tab describes the reproducibility checks that were applied when the results were created. The Past versions tab lists the development history.

Great! Since the R Markdown file has been committed to the Git repository, you know the exact version of the code that produced these results.

Great job! The global environment was empty. Objects defined in the global environment can affect the analysis in your R Markdown file in unknown ways. For reproduciblity it’s best to always run the code in an empty environment.

The command set.seed(20200712) was run prior to running

the code in the R Markdown file. Setting a seed ensures that any results

that rely on randomness, e.g. subsampling or permutations, are

reproducible.

Great job! Recording the operating system, R version, and package versions is critical for reproducibility.

Nice! There were no cached chunks for this analysis, so you can be confident that you successfully produced the results during this run.

Great job! Using relative paths to the files within your workflowr project makes it easier to run your code on other machines.

Great! You are using Git for version control. Tracking code development and connecting the code version to the results is critical for reproducibility.

The results in this page were generated with repository version 070a399. See the Past versions tab to see a history of the changes made to the R Markdown and HTML files.

Note that you need to be careful to ensure that all relevant files for

the analysis have been committed to Git prior to generating the results

(you can use wflow_publish or

wflow_git_commit). workflowr only checks the R Markdown

file, but you know if there are other scripts or data files that it

depends on. Below is the status of the Git repository when the results

were generated:

Ignored files:

Ignored: .Rproj.user/

Ignored: data/1M_neurons_filtered_gene_bc_matrices_h5.h5

Ignored: data/293t/

Ignored: data/293t_3t3_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: data/293t_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: data/5k_Human_Donor1_PBMC_3p_gem-x_5k_Human_Donor1_PBMC_3p_gem-x_count_sample_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/5k_Human_Donor2_PBMC_3p_gem-x_5k_Human_Donor2_PBMC_3p_gem-x_count_sample_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/5k_Human_Donor3_PBMC_3p_gem-x_5k_Human_Donor3_PBMC_3p_gem-x_count_sample_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/5k_Human_Donor4_PBMC_3p_gem-x_5k_Human_Donor4_PBMC_3p_gem-x_count_sample_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/97516b79-8d08-46a6-b329-5d0a25b0be98.h5ad

Ignored: data/Parent_SC3v3_Human_Glioblastoma_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.tar.gz

Ignored: data/brain_counts/

Ignored: data/cl.obo

Ignored: data/cl.owl

Ignored: data/jurkat/

Ignored: data/jurkat:293t_50:50_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: data/jurkat_293t/

Ignored: data/jurkat_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: data/pbmc20k/

Ignored: data/pbmc20k_seurat/

Ignored: data/pbmc3k.csv

Ignored: data/pbmc3k.csv.gz

Ignored: data/pbmc3k.h5ad

Ignored: data/pbmc3k/

Ignored: data/pbmc3k_bpcells_mat/

Ignored: data/pbmc3k_export.mtx

Ignored: data/pbmc3k_matrix.mtx

Ignored: data/pbmc3k_seurat.rds

Ignored: data/pbmc4k_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: data/pbmc_1k_v3_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/pbmc_1k_v3_raw_feature_bc_matrix.h5

Ignored: data/refdata-gex-GRCh38-2020-A.tar.gz

Ignored: data/seurat_1m_neuron.rds

Ignored: data/t_3k_filtered_gene_bc_matrices.tar.gz

Ignored: r_packages_4.4.1/

Ignored: r_packages_4.5.0/

Untracked files:

Untracked: .claude/

Untracked: CLAUDE.md

Untracked: analysis/bioc.Rmd

Untracked: analysis/bioc_scrnaseq.Rmd

Untracked: analysis/chick_weight.Rmd

Untracked: analysis/likelihood.Rmd

Untracked: bpcells_matrix/

Untracked: data/Caenorhabditis_elegans.WBcel235.113.gtf.gz

Untracked: data/GCF_043380555.1-RS_2024_12_gene_ontology.gaf.gz

Untracked: data/arab.rds

Untracked: data/astronomicalunit.csv

Untracked: data/femaleMiceWeights.csv

Untracked: data/lung_bcell.rds

Untracked: m3/

Untracked: women.json

Unstaged changes:

Modified: analysis/isoform_switch_analyzer.Rmd

Modified: analysis/linear_models.Rmd

Note that any generated files, e.g. HTML, png, CSS, etc., are not included in this status report because it is ok for generated content to have uncommitted changes.

These are the previous versions of the repository in which changes were

made to the R Markdown (analysis/fourier_transform.Rmd) and

HTML (docs/fourier_transform.html) files. If you’ve

configured a remote Git repository (see ?wflow_git_remote),

click on the hyperlinks in the table below to view the files as they

were in that past version.

| File | Version | Author | Date | Message |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rmd | 070a399 | Dave Tang | 2026-02-02 | Introduction to the Fourier Transform |

What is the Fourier Transform?

The Fourier Transform is a mathematical technique that decomposes a signal into its constituent frequencies. Named after French mathematician Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier, it transforms data from the time domain (or spatial domain) into the frequency domain.

If you hear a musical chord (when you play three or more notes simultaneously to create a harmonic sound), the Fourier Transform can tell you which individual notes make up that chord and how loud each note is.

Why is it useful?

The Fourier Transform is fundamental in many fields:

- Signal processing: Filtering noise from audio or images

- Bioinformatics: Analysing periodic patterns in DNA sequences, spectroscopy data

- Image processing: JPEG compression, edge detection

- Physics: Quantum mechanics, optics, acoustics

The intuition

Any periodic signal can be represented as a sum of sine and cosine waves of different frequencies. The Fourier Transform finds the amplitude and phase of each frequency component.

Let’s start with a simple example: creating a signal from known frequencies.

- Hertz is a unit that measures frequency: how many times something happens per second.

- 100 Hz means something is happening 100 times per second.

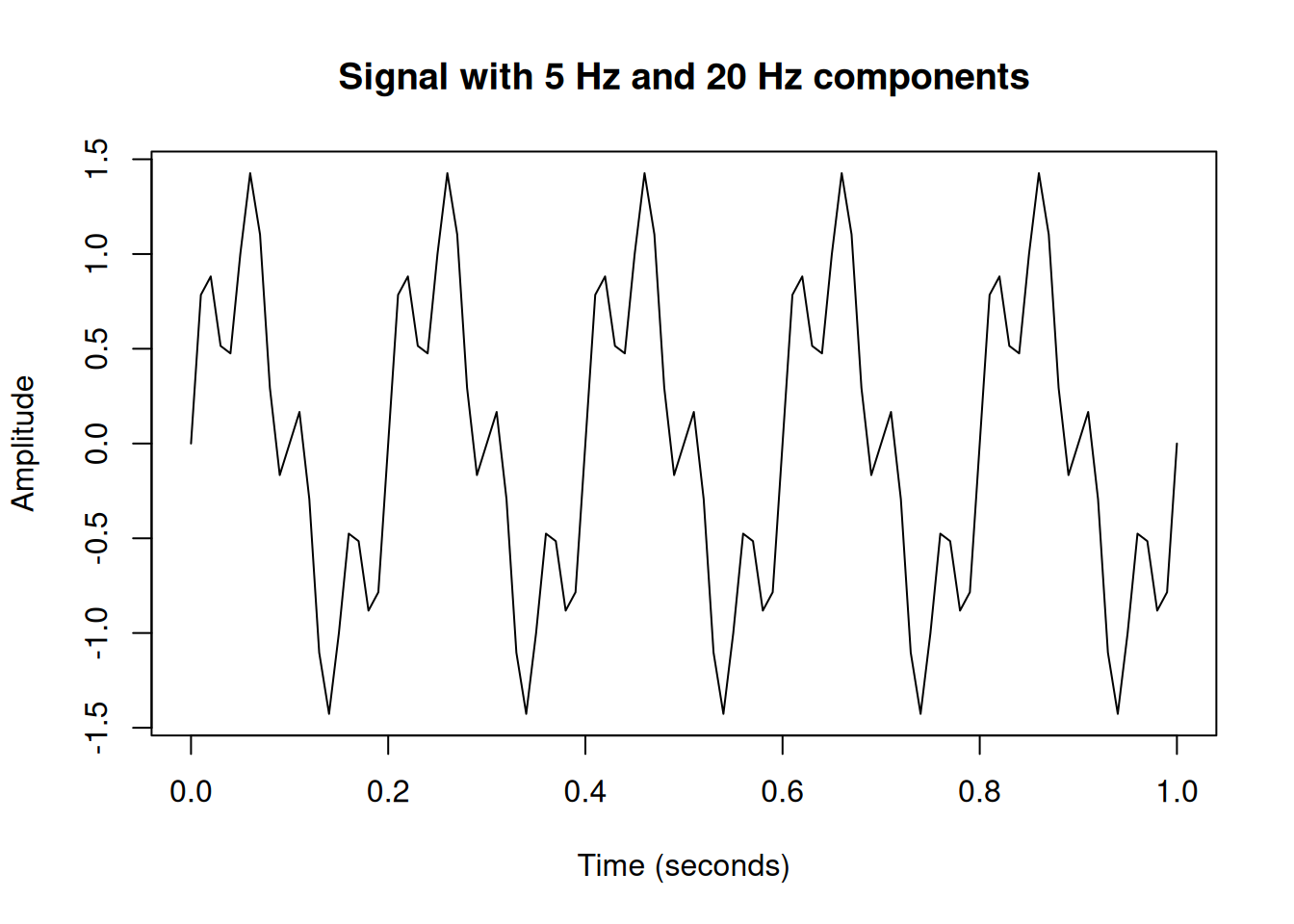

# Create a time vector (1 second of data sampled at 100 Hz)

sample_rate <- 100

duration <- 1

t <- seq(0, duration, by = 1/sample_rate)

# Create a signal with two frequencies: 5 Hz and 20 Hz

freq1 <- 5

freq2 <- 20

signal <- sin(2 * pi * freq1 * t) + 0.5 * sin(2 * pi * freq2 * t)

plot(t, signal, type = "l",

xlab = "Time (seconds)",

ylab = "Amplitude",

main = "Signal with 5 Hz and 20 Hz components")

Looking at this signal, it’s not immediately obvious that it’s composed of two sine waves. Let’s use the Fourier Transform to reveal the hidden frequencies.

The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) in R

R provides the fft() function which implements the Fast

Fourier Transform, an efficient algorithm for computing the Discrete

Fourier Transform (DFT).

# Compute the FFT

fft_result <- fft(signal)

# The FFT returns complex numbers

head(fft_result)[1] -8.437695e-15+ 0.0000000i 7.025444e-03- 0.2257903i

[3] 3.167017e-02- 0.5084300i 9.109146e-02- 0.9733405i

[5] 2.734064e-01- 2.1861049i 7.768581e+00-49.5475020iThe FFT returns complex numbers. The magnitude (absolute value) tells us the amplitude of each frequency component. The phase (argument) tells us the phase shift.

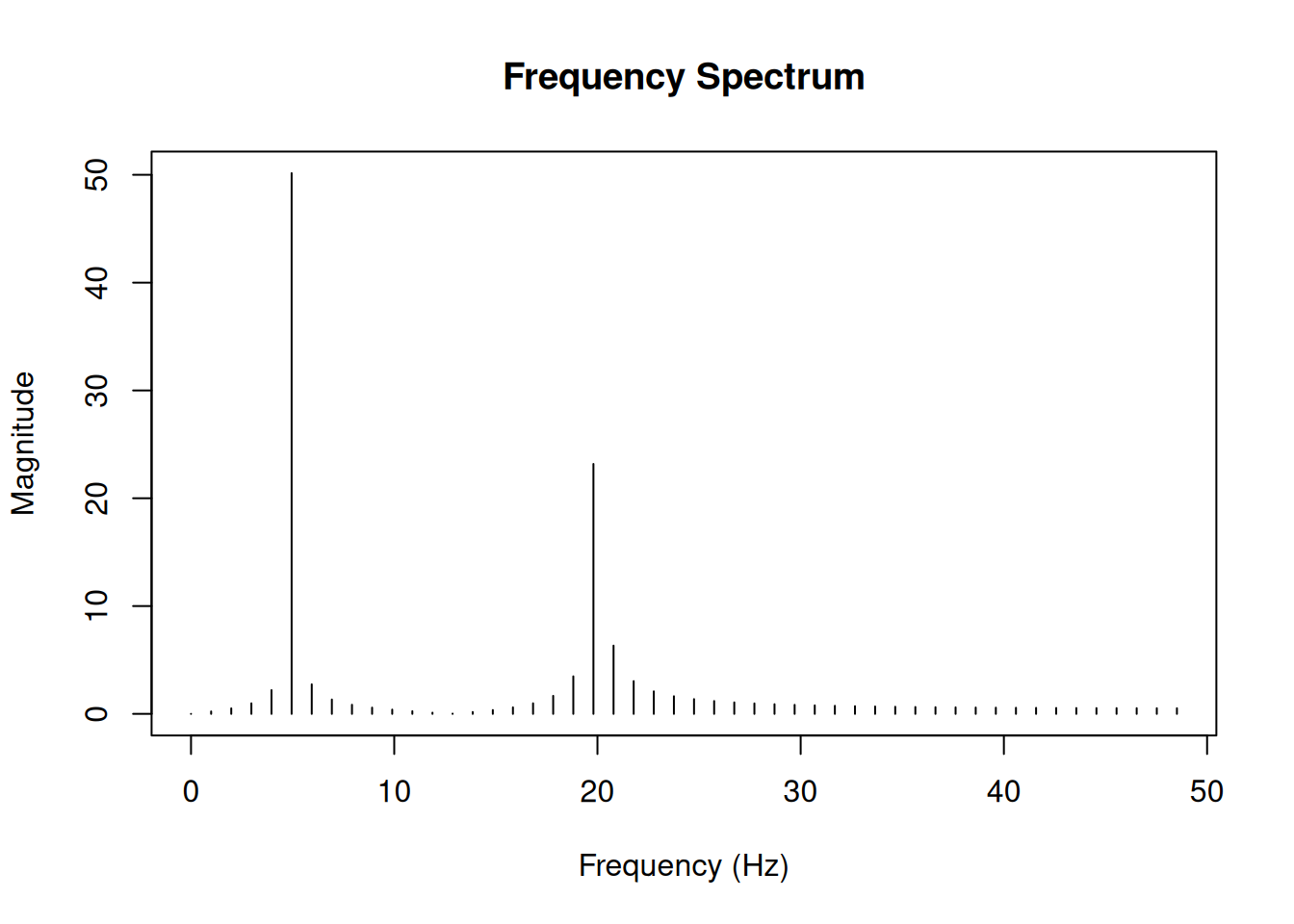

# Calculate magnitude

magnitude <- Mod(fft_result)

# Create frequency axis

n <- length(signal)

freq <- (0:(n-1)) * sample_rate / n

# Plot only the first half (positive frequencies)

# The FFT output is symmetric for real signals

half_n <- floor(n/2)

plot(freq[1:half_n], magnitude[1:half_n], type = "h",

xlab = "Frequency (Hz)",

ylab = "Magnitude",

main = "Frequency Spectrum")

Notice the peaks at 5 Hz and 20 Hz - exactly the frequencies we used to create our signal! The peak at 5 Hz is twice as high as the peak at 20 Hz, reflecting the amplitude ratio (1.0 vs 0.5) in our original signal.

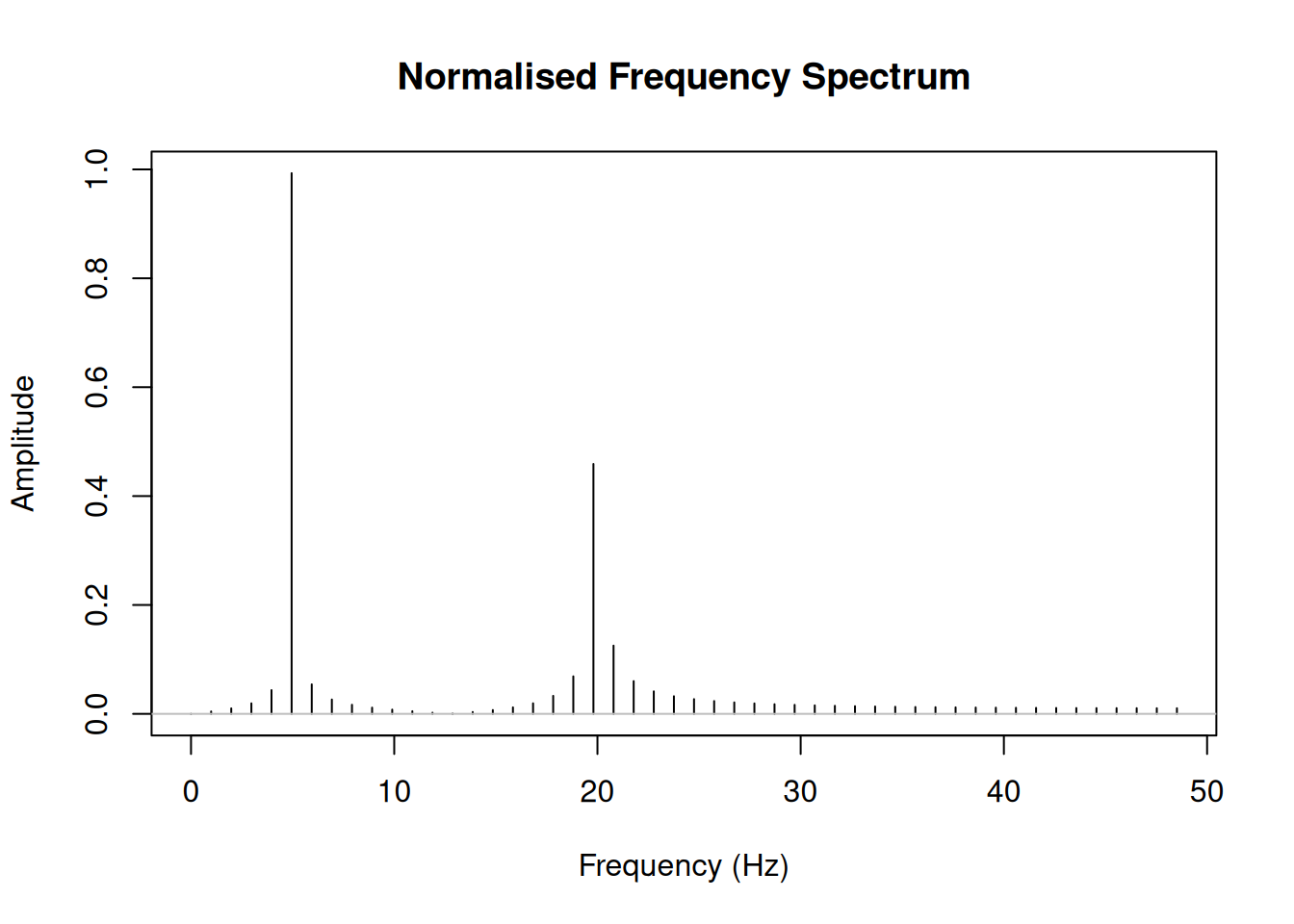

Normalising the FFT output

To get meaningful amplitude values, we need to normalise the FFT output.

# Normalise by the number of samples

# Multiply by 2 for single-sided spectrum (except DC component)

magnitude_normalised <- (2 * Mod(fft_result) / n)[1:half_n]

magnitude_normalised[1] <- magnitude_normalised[1] / 2 # DC component

plot(freq[1:half_n], magnitude_normalised, type = "h",

xlab = "Frequency (Hz)",

ylab = "Amplitude",

main = "Normalised Frequency Spectrum")

# Add points to highlight peaks

abline(h = 0, col = "gray")

Now the amplitudes approximately match our original signal (1.0 for 5 Hz and 0.5 for 20 Hz).

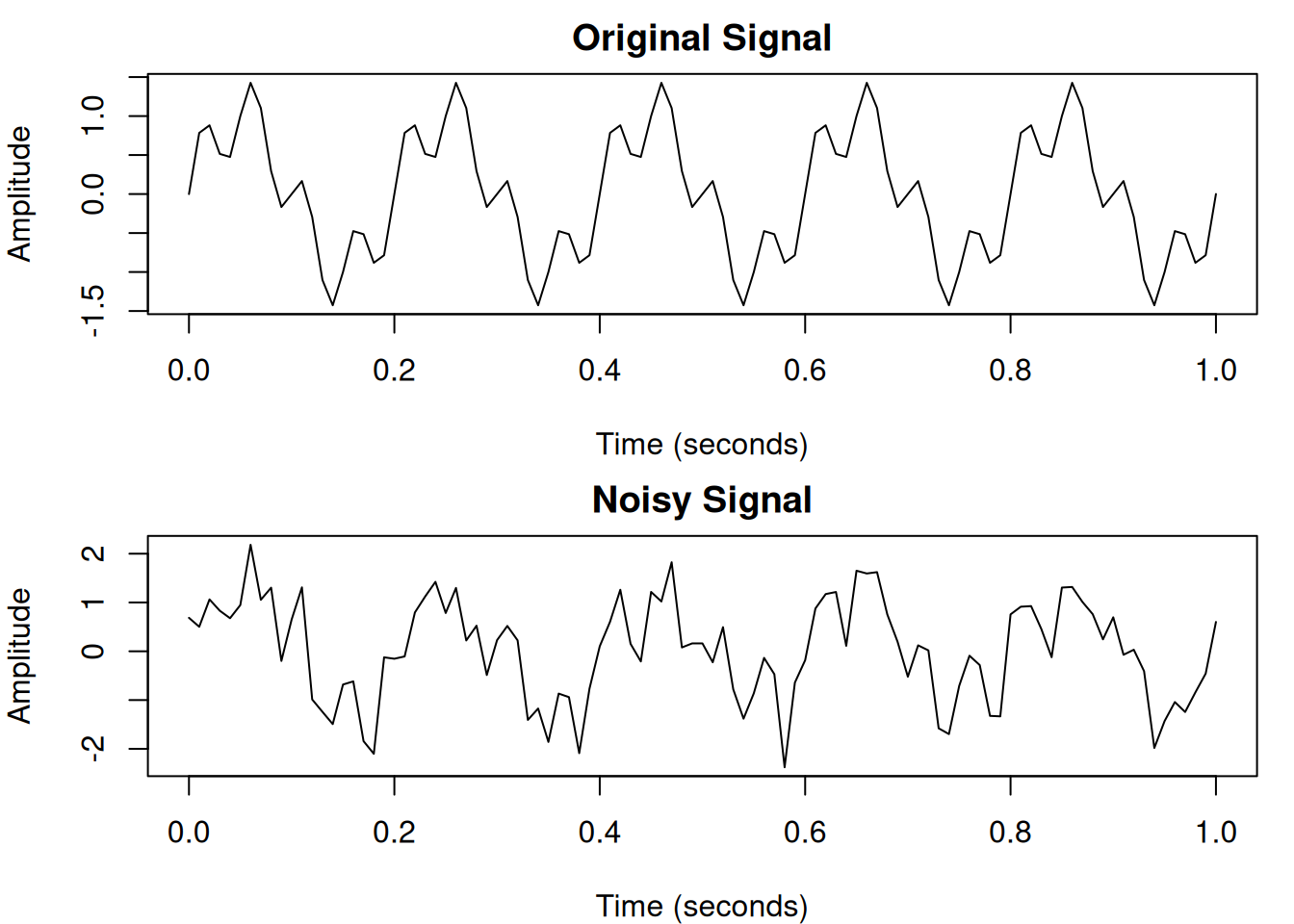

A practical example: Removing noise

One common application is filtering noise from a signal. Let’s add noise to our signal and then filter it out.

# Add random noise

set.seed(42)

noisy_signal <- signal + rnorm(length(signal), sd = 0.5)

par(mfrow = c(2, 1), mar = c(4, 4, 2, 1))

plot(t, signal, type = "l",

xlab = "Time (seconds)", ylab = "Amplitude",

main = "Original Signal")

plot(t, noisy_signal, type = "l",

xlab = "Time (seconds)", ylab = "Amplitude",

main = "Noisy Signal")

par(mfrow = c(1, 1))# FFT of noisy signal

fft_noisy <- fft(noisy_signal)

# Create a low-pass filter (keep frequencies below 25 Hz)

cutoff <- 25

filter_mask <- rep(0, n)

freq_indices <- which(freq <= cutoff | freq >= (sample_rate - cutoff))

filter_mask[freq_indices] <- 1

# Apply filter

fft_filtered <- fft_noisy * filter_mask

# Inverse FFT to get back to time domain

filtered_signal <- Re(fft(fft_filtered, inverse = TRUE) / n)

par(mfrow = c(2, 1), mar = c(4, 4, 2, 1))

plot(t, noisy_signal, type = "l", col = "gray",

xlab = "Time (seconds)", ylab = "Amplitude",

main = "Noisy vs Filtered Signal")

lines(t, filtered_signal, col = "blue", lwd = 2)

legend("topright", legend = c("Noisy", "Filtered"),

col = c("gray", "blue"), lty = 1, lwd = c(1, 2))

plot(t, signal, type = "l", col = "black",

xlab = "Time (seconds)", ylab = "Amplitude",

main = "Original vs Filtered Signal")

lines(t, filtered_signal, col = "blue", lwd = 2, lty = 2)

legend("topright", legend = c("Original", "Filtered"),

col = c("black", "blue"), lty = c(1, 2), lwd = c(1, 2))

par(mfrow = c(1, 1))Understanding the mathematics

The Discrete Fourier Transform is defined as:

\[X_k = \sum_{n=0}^{N-1} x_n \cdot e^{-i 2\pi k n / N}\]

Where:

- \(x_n\) is the input signal at time point \(n\)

- \(X_k\) is the complex amplitude at frequency \(k\)

- \(N\) is the total number of samples

- \(e^{-i 2\pi k n / N}\) represents complex sinusoids (from Euler’s formula: \(e^{i\theta} = \cos\theta + i\sin\theta\))

The inverse transform reconstructs the original signal:

\[x_n = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} X_k \cdot e^{i 2\pi k n / N}\]

Computing DFT manually

Let’s verify our understanding by computing the DFT manually for a small signal.

# Simple signal

x <- c(1, 2, 3, 4)

N <- length(x)

# Manual DFT

manual_dft <- function(x) {

N <- length(x)

X <- complex(N)

for (k in 0:(N-1)) {

for (n in 0:(N-1)) {

X[k+1] <- X[k+1] + x[n+1] * exp(-1i * 2 * pi * k * n / N)

}

}

return(X)

}

# Compare manual vs fft()

manual_result <- manual_dft(x)

fft_result <- fft(x)

data.frame(

k = 0:(N-1),

manual_real = round(Re(manual_result), 6),

manual_imag = round(Im(manual_result), 6),

fft_real = round(Re(fft_result), 6),

fft_imag = round(Im(fft_result), 6)

) k manual_real manual_imag fft_real fft_imag

1 0 10 0 10 0

2 1 -2 2 -2 2

3 2 -2 0 -2 0

4 3 -2 -2 -2 -2The results match! The FFT is simply a faster algorithm (\(O(N \log N)\) vs \(O(N^2)\)) for computing the same thing.

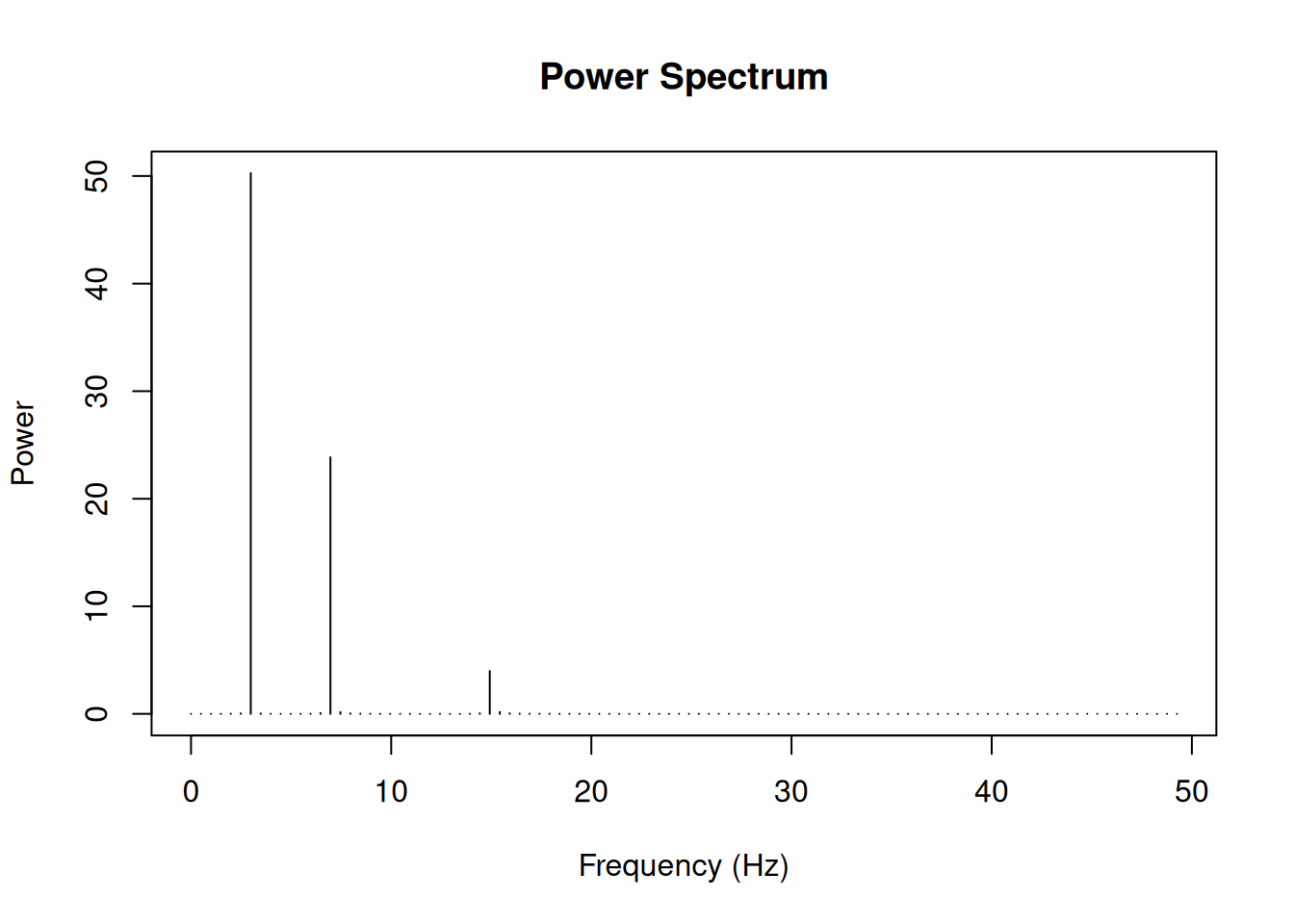

Power spectrum

The power spectrum shows the distribution of signal power across frequencies. It’s computed as the squared magnitude of the FFT.

# Create a more complex signal

t_long <- seq(0, 2, by = 1/sample_rate)

complex_signal <- sin(2 * pi * 3 * t_long) +

0.7 * sin(2 * pi * 7 * t_long) +

0.3 * sin(2 * pi * 15 * t_long)

# Compute power spectrum

fft_complex <- fft(complex_signal)

n_long <- length(complex_signal)

power <- (Mod(fft_complex)^2) / n_long

freq_long <- (0:(n_long-1)) * sample_rate / n_long

# Plot

half_n_long <- floor(n_long/2)

plot(freq_long[1:half_n_long], power[1:half_n_long], type = "h",

xlab = "Frequency (Hz)",

ylab = "Power",

main = "Power Spectrum")

Summary

Key takeaways:

- The Fourier Transform converts signals from time domain to frequency domain

- Use

fft()in R for the Fast Fourier Transform - The FFT returns complex numbers; use

Mod()for magnitude,Arg()for phase - For real signals, the FFT output is symmetric - only the first half is needed

- Remember to normalise by dividing by the number of samples

sessionInfo()R version 4.5.0 (2025-04-11)

Platform: x86_64-pc-linux-gnu

Running under: Ubuntu 24.04.3 LTS

Matrix products: default

BLAS: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/openblas-pthread/libblas.so.3

LAPACK: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/openblas-pthread/libopenblasp-r0.3.26.so; LAPACK version 3.12.0

locale:

[1] LC_CTYPE=en_US.UTF-8 LC_NUMERIC=C

[3] LC_TIME=en_US.UTF-8 LC_COLLATE=en_US.UTF-8

[5] LC_MONETARY=en_US.UTF-8 LC_MESSAGES=en_US.UTF-8

[7] LC_PAPER=en_US.UTF-8 LC_NAME=C

[9] LC_ADDRESS=C LC_TELEPHONE=C

[11] LC_MEASUREMENT=en_US.UTF-8 LC_IDENTIFICATION=C

time zone: Etc/UTC

tzcode source: system (glibc)

attached base packages:

[1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

other attached packages:

[1] workflowr_1.7.1

loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

[1] vctrs_0.6.5 httr_1.4.7 cli_3.6.5 knitr_1.50

[5] rlang_1.1.6 xfun_0.52 stringi_1.8.7 processx_3.8.6

[9] promises_1.3.3 jsonlite_2.0.0 glue_1.8.0 rprojroot_2.0.4

[13] git2r_0.36.2 htmltools_0.5.8.1 httpuv_1.6.16 ps_1.9.1

[17] sass_0.4.10 rmarkdown_2.29 jquerylib_0.1.4 tibble_3.3.0

[21] evaluate_1.0.3 fastmap_1.2.0 yaml_2.3.10 lifecycle_1.0.4

[25] whisker_0.4.1 stringr_1.5.1 compiler_4.5.0 fs_1.6.6

[29] pkgconfig_2.0.3 Rcpp_1.0.14 rstudioapi_0.17.1 later_1.4.2

[33] digest_0.6.37 R6_2.6.1 pillar_1.10.2 callr_3.7.6

[37] magrittr_2.0.3 bslib_0.9.0 tools_4.5.0 cachem_1.1.0

[41] getPass_0.2-4